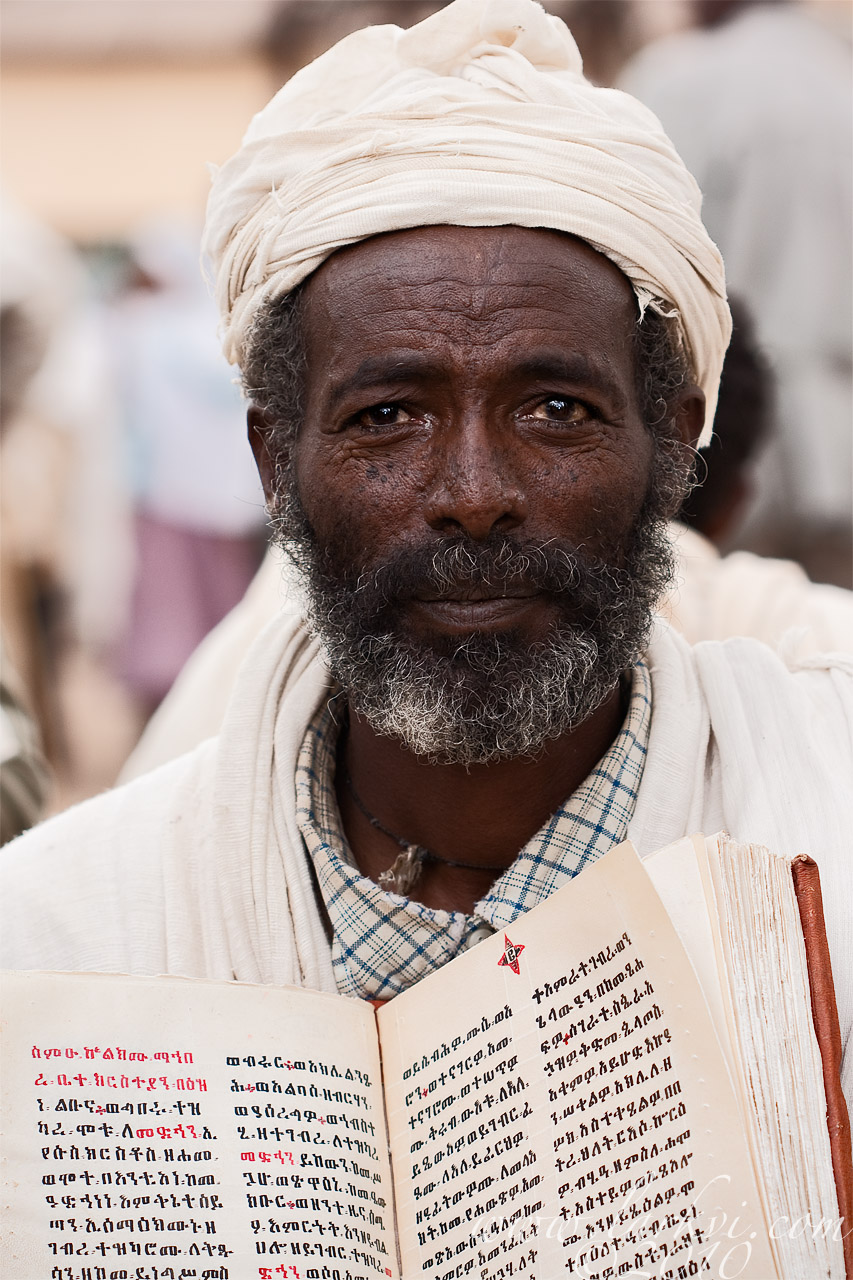

Qes Deseta Altah was one of my informants for my dissertation research on Ethiopian scribal production. I took this portrait while meeting with him at his home in Gelawdios, outside of Bahir Dar.

Tag: Scribe

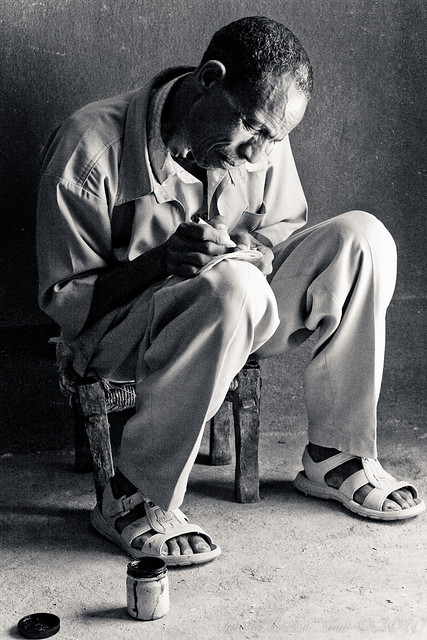

Making Ink, Axum, Ethiopia, 2009

Melaka Tsehai burns the oil off of an addition of nug (an oilseed) to the carbonized grains, leaves, and earths that serve as the base for black ink. Various implments of the scribe’s crafts are on the ground beside him. Also, lest any one accuse me of having done the opposite–I have actually *de*-saturated his spectacular neon orange hat. A truly one-of-a-kind hat.

Ashmelas WoldeGabriel at Work, Axum, Tigray, Ethiopia, 2009

Scribe, Book Market, Axum, 2009

Kes Fente, Gälawdios, Amhara, Ethiopia, July 2009

Liqa Kahunat Ajugu, Gälawdios, Amhara, Ethiopia, July 2009

Kes Mogas, Gälawdios, Amhara, Ethiopia, July 2009

Kes Te’ubo, Lalibela, Lasta, Ethiopia June 2009

Kes Te’ubo is a local administrator and a scribe/illustrator in Lalibela. He makes wonderful, vivid colors out of powdered natural materials, mainly flower petals, roots, and leaves. Here, he is demonstrating his pen-cutting technique on a piece of native bamboo, known as ‘shamboko,’ which is the primary material used for traditional pens in Ethiopia (some other materials are mainly used for magical writing, and there is a tradition that quills were also used in the past.

Interviewing Te’ubo was interesting, as he was arrested on false charges between two of our meetings and thrown into the local lock-up. It was the first time I visited a jail in Ethiopia, though it was the temporary local jail, and not the prison proper. He was let out later that day, and the charges were apparently thrown out by the magistrate, but I briefly thought I would have to finish the interviews in prison.

Haleka Woldegabriel, Axum, Tigray, Ethiopia, April 2009

Haleka Woldegabriel is a artisan in Axum, primarily producing fairly low-quality woodcrafts for the tourist shop market, but in the past, he produced books and magic scrolls. Like many other scribes, he says that he has had to give it up because the economic situation of the scribe is no longer tenable, and other crafts are significantly more profitable. Haleka Woldegabriel is interesting for being the first scribe I have met so far to use steel pen-nibs in his writing, rather than bamboo pens.

He’s holding an incomplete magic scroll–he sends them to others for painting when the writing is done.

Keshi Mengistu Eyesus, Mek’ele, Tigray, April 2009

Keshi Mengistu Eyesu is a woodworker, scribe, and painter working in Mek’ele. He is a consummate artist, and, though he focuses on woodworking (more profitable) now, his scribal works are excellent. Though he produces them with an ink wash, to "antique" them, they need no selling as antiques, as they are excellent modern examples of traditional Ethiopian art (I’m thinking of buying one myself). Here you can see him finishing off a healing scroll with red detailing, while a carved wooden processional cross of his production sits in the background.

Magic scrolls exist in a continuum with church scrolls in Ethiopian Christianity. As in many societies with low literacy rates, writing is associated with the ability to perform magic. In a Christian society like Ethiopia, this is doubly so, as people are familiar with the magical/miraculous abilities granted to the priesthood through the recitation of written documents of the Church. The learned liturgical specialists of the Church, däbtäras, are also suspected as magicians–the word for magician is däbtära–because they have access to knowledge which is secret, both because it requires literacy, and because it is actually secret. Church scrolls, containing prayers invoking the names of angels, Jesus, and the BVM transition into magic scrolls when, in order to grant additional power or a different kind of power, the secret names of devils, demons, and magical entities are used. Apparently, some of these names are written invisibly in a process that I was poorly able to understand, though I am working on it. In addition to scrolls, Ethiopians keep alive a tradition of amulets, both those familiar from Orthodox Judaism, containing biblical passages, and those of a less religious and more magical nature.